I Just Wanted Emacs to Look Nice — Using 24-Bit Color in Terminals

Thanks to some coworkers and David Wilson’s Emacs from Scratch playlist, I’ve been getting back into Emacs. The community is more vibrant than the last time I looked, and LSP brings modern completion and inline type checking.

David’s Emacs looks so fancy — I want nice colors and fonts too, especially my preferred themes like Solarized.

From desktop environments, Emacs automatically supports 24-bit color.

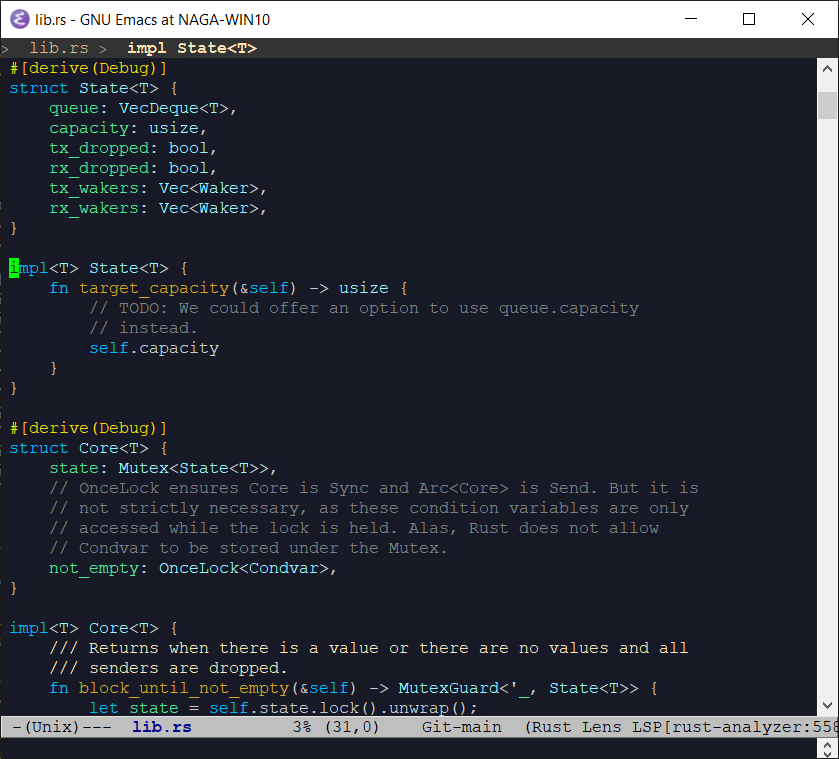

But, since I work on infrastructure, I’ve lived primarily in terminals for years. And my Emacs looks like:

It turns out, for years, popular terminals have supported 24-bit color. And yet they’re rarely used.

Like everything else, it boil down to legacy and politics. Control codes are a protocol, and changes to that protocol take time to propagate, especially with missteps along the way.

This post is two things:

- how to enable true-color support in the terminal environments I use, and

- how my desire for nice colors in Emacs led to poring over technical standards from the 70s, 80s, and 90s, wondering how we got to this point.

NOTE: I did my best, but please forgive any terminology slip-ups or false histories. I grew up on VGA text mode UIs, but never used a hardware terminal and wasn’t introduced to unix until much later.

ANSI Escape Codes

Early hardware terminals offered their own, incompatible, control code schemes. That made writing portable software hard, so ANSI standardized the protocol, while reserving room for expansion and vendor-specific capabilities.

ANSI escape codes date back to the 70s. They cover a huge range of functionality, but since this post is focused on colors, I’m mostly interested in SGR (Select Graphics Rendition), which allows configuring a variety of character display attributes:

- bold or intensity

- italics (not frequently supported)

- blink

- foreground and background colors

- and a bunch of other stuff. You can look at Wikipedia.

3-, 4-, and 8-bit Color

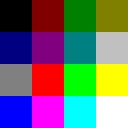

When color was introduced, there were eight. Black, white, the additive primaries, and the subtractive primaries. The eight corners of an RGB color cube.

Later, a bright (or bold) bit added eight more; “bright black” being dark gray.

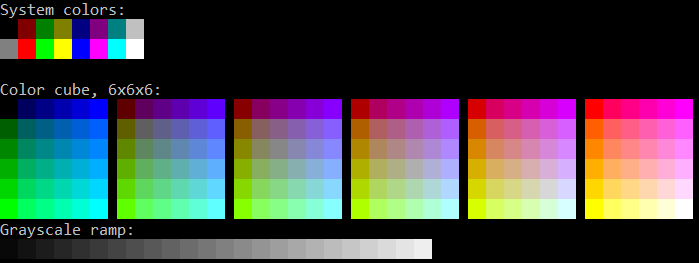

In 1999, Todd Larason patched xterm to add support for 256 colors. He chose a palette that filled out the RGB color cube with a 6x6x6 interior sampling and added a 24-entry finer-precision grayscale ramp.

NOTE: There’s a rare, but still-supported, 88-color variant with a 4x4x4 color cube and 8-entry grayscale ramp, primarily to reduce the use of historically-limited X11 color objects.

NOTE: We’ll debug this later, but Todd’s patch to add 256-color support to xterm used semicolons as the separator between the ANSI SGR command 48 and the color index, which set off a chain reaction of ambiguity we’re still dealing with today.

Where Did 24-Bit Color Support Come From?

It’s well-documented how to send 8-bit and 24-bit colors to compatible terminals. Per Wikipedia:

ESC[38;5;<n>m sets foreground color n per the palettes above.

ESC[38;2;<r>;<g>;<b>m sets foreground color (r, g, b).

(Again, that confusion about semicolons vs. colons, and an unused colorspace ID if colons are used. We’ll get to the bottom of that soon.)

But why 5? Why 2? How did any of this come about? I’d struggled enough with unexpected output that it was time to discover the ground truth.

Finding and reading original sources led me to construct the following narrative:

- In the 70s, ANSI standardized terminal escape sequences, resulting in ANSI X3.64 and the better-known ECMA-48.

- The first edition of ECMA-48 is lost to time, but it probably looks much like ANSI X3.64.

- The 2nd

edition

of ECMA-48 (1979) allocated SGR parameters 30-37 and 40-47 for setting

3-bit foreground and background colors, respectively.

- By the way, these standards use the word “parameter” to mean command, and “subparameter” to mean argument, if applicable.

- The 3rd edition (1984) introduced the concept of an implementation-defined default color for both foreground and background, and allocated parameters 39 and 49, respectively.

- Somewhere in this timeline, vendors did ship hardware terminals with richer color support. The Wyse WY-370 introduced new color modes, including a direct-indexed 64-color palette. (See Page 86 of its Programmer’s Guide.)

- 38 and 48 are the most important parameters for selecting colors

today, but they weren’t allocated by either the

4th

(1986) or

5th

(1991) editions. So where did they come from? The 5th edition gives

a clue:

reserved for future standardization; intended for setting character foreground colour as specified in ISO 8613-6 [CCITT Recommendation T.416]

-

ISO 8613 was a boondoggle of a project intended to standardize and replace all proprietary document file formats. You’ve never heard of it, so it obviously failed. But its legacy lives on – ISO 8613-6 (ITU T.416) (1993) built on ECMA-48’s codes and defined parameters 38 and 48 as extended foreground and background color modes, respectively.

The first parameter element indicates a choice between:

- 0 implementation defined (only applicable for the character foreground colour)

- 1 transparent;

- 2 direct colour in RGB space;

- 3 direct colour in CMY space;

- 4 direct colour in CMYK space;

- 5 indexed colour.

There we go! That is why 5 is used for 256-color mode and 2 is 24-bit RGB.

Careful reading also gives a clue as to the semicolon vs. colon syntax screw-up. Note the subtle use of the term “parameter element” vs. “parameter”.

If you read ISO 8613-6 (ITU T.416) and ECMA-48 closely, it’s not explicitly stated, but they seem to indicate that unknown parameters for commands like “select graphics rendition” should be ignored. And parameters are separated with semicolons.

That implies ESC[38;5;3m should be interpreted, in terminals that

don’t support SGR 38, as “unknown, ignored (38)”, “blinking (5)”, and

“italicized (3)”. The syntax should use colons to separate

sub-parameter components, but something got lost along the way.

(Now, in practice, programs are told how to communicate with their terminals via the TERM variable and the terminfo database, so I don’t know how much pain occurs in reality.)

Thomas Dickey has done a great job documenting the history of ncurses and xterm, and, lo and behold, explains exactly the origin of the ambiguous syntax:

We used semicolon (like other SGR parameters) for separating the R/G/B values in the escape sequence, since a copy of ITU T.416 (ISO-8613-6) which presumably clarified the use of colon for this feature was costly.

Using semicolon was incorrect because some applications could expect their parameters to be order-independent. As used for the R/G/B values, that was order-dependent. The relevant information, by the way, is part of ECMA-48 (not ITU T.416, as mentioned in Why only 16 (or 256) colors?). Quoting from section 5.4.2 of ECMA-48, page 12, and adding emphasis (not in the standard):

Each parameter sub-string consists of one or more bit combinations from 03/00 to 03/10; the bit combinations from 03/00 to 03/09 represent the digits ZERO to NINE; bit combination 03/10 may be used as a separator in a parameter sub-string, for example, to separate the fractional part of a decimal number from the integer part of that number.

and later on page 78, in 8.3.117 SGR – SELECT GRAPHIC RENDITION, the description of SGR 38:

(reserved for future standardization; intended for setting character foreground colour as specified in ISO 8613-6 [CCITT Recommendation T.416])

Of course you will immediately recognize that 03/10 is ASCII colon, and that ISO 8613-6 necessarily refers to the encoding in a parameter sub-string. Or perhaps you will not.

So it’s all because the ANSI and ISO standards are ridiculously

expensive (to this day, these crappy PDF scans from the 90s and

earlier are $200 USD!) and because they use a baroque syntax to denote

ASCII characters. While writing this post, I had to keep man ascii

open to match, for example, 03/10 to colon and 03/11 to semicolon.

I guess it’s how standards were written back then. A Hacker News

thread in the context of WezTerm gives more

detail.

So, to recap in the timeline:

- 1999: Thomas Dickey merged Todd Larason’s 256-color patches with ambiguous semicolon syntax.

- 2006: Konsole added support for 256-color and 24-bit truecolor using the same ambiguous syntax as xterm, with a follow-on discussion about colons vs. semicolons. The issue was noticed, but semicolon syntax was adopted anyway.

- 2012: Thomas Dickey fixed xterm to accept the standards-compliant syntax.

- 2016: Windows 10’s built-in console gained ANSI escape code support, including 24-bit colors. Unfortunately with the ambiguous semicolon syntax.

- 2019: Windows Terminal is released, with ANSI escape code support, but also using ambiguous semicolon syntax.

- 2022: Microsoft announced ecosystem-wide migration from the legacy framebuffer-based VGA-style console subsystem to ANSI terminal emulation, specifically using xterm as a guide.

- 2022: Konsole gains support for standards-compliant syntax.

Okay, here’s what we’ve established:

- ANSI codes are widely supported, even on Windows.

- Truecolor support is either widely supported or (for example, on the Linux text mode terminal) at least recognized and mapped to a more limited palette.

- Semicolon syntax is the most compatible, though the unambiguous colon syntax is slowly spreading.

I wrote a small colortest.rs program to test color support and attributes like reverse and italics to confirm the above in every terminal I use.

Terminfo

Now that we’ve established terminal capabilities and how to use them, the next trick is to convince software of varying lineages to detect and use the best color support available.

Typically, this is done with the old terminfo library (or the even older termcap).

Terminfo provides a database of terminal capabilities and the ability

to generate appropriate escape sequences. The TERM environment

variable tells programs which terminfo record to use. Its value is

automatically forwarded over ssh connections.

Terminfo uses ridiculous command names: infocmp, tic, toe. (Not

to be confused with the unrelated tac.)

To see the list of terminfo records installed on your host, run toe

-a. (Do we /really/ need to install support for every legacy hardware

terminal on modern machines? Good luck even finding a hardware

terminal these days. They’re collector’s items.)

infocmp is how you inspect the capabilities of a specific terminfo

record.

$ infocmp xterm-256color

# Reconstructed via infocmp from file: /lib/terminfo/x/xterm-256color

xterm-256color|xterm with 256 colors,

am, bce, ccc, km, mc5i, mir, msgr, npc, xenl,

colors#0x100, cols#80, it#8, lines#24, pairs#0x10000,

acsc=``aaffggiijjkkllmmnnooppqqrrssttuuvvwwxxyyzz{{||}}~~,

bel=^G, blink=\E[5m, bold=\E[1m, cbt=\E[Z, civis=\E[?25l,

clear=\E[H\E[2J, cnorm=\E[?12l\E[?25h, cr=\r,

csr=\E[%i%p1%d;%p2%dr, cub=\E[%p1%dD, cub1=^H,

cud=\E[%p1%dB, cud1=\n, cuf=\E[%p1%dC, cuf1=\E[C,

cup=\E[%i%p1%d;%p2%dH, cuu=\E[%p1%dA, cuu1=\E[A,

cvvis=\E[?12;25h, dch=\E[%p1%dP, dch1=\E[P, dim=\E[2m,

dl=\E[%p1%dM, dl1=\E[M, ech=\E[%p1%dX, ed=\E[J, el=\E[K,

el1=\E[1K, flash=\E[?5h$<100/>\E[?5l, home=\E[H,

hpa=\E[%i%p1%dG, ht=^I, hts=\EH, ich=\E[%p1%d@,

il=\E[%p1%dL, il1=\E[L, ind=\n, indn=\E[%p1%dS,

initc=\E]4;%p1%d;rgb:%p2%{255}%*%{1000}%/%2.2X/%p3%{255}%*%{1000}%/%2.2X/%p4%{255}%*%{1000}%/%2.2X\E\\,

invis=\E[8m, is2=\E[!p\E[?3;4l\E[4l\E>, kDC=\E[3;2~,

kEND=\E[1;2F, kHOM=\E[1;2H, kIC=\E[2;2~, kLFT=\E[1;2D,

kNXT=\E[6;2~, kPRV=\E[5;2~, kRIT=\E[1;2C, ka1=\EOw,

ka3=\EOy, kb2=\EOu, kbeg=\EOE, kbs=^?, kc1=\EOq, kc3=\EOs,

kcbt=\E[Z, kcub1=\EOD, kcud1=\EOB, kcuf1=\EOC, kcuu1=\EOA,

kdch1=\E[3~, kend=\EOF, kent=\EOM, kf1=\EOP, kf10=\E[21~,

kf11=\E[23~, kf12=\E[24~, kf13=\E[1;2P, kf14=\E[1;2Q,

kf15=\E[1;2R, kf16=\E[1;2S, kf17=\E[15;2~, kf18=\E[17;2~,

kf19=\E[18;2~, kf2=\EOQ, kf20=\E[19;2~, kf21=\E[20;2~,

kf22=\E[21;2~, kf23=\E[23;2~, kf24=\E[24;2~,

kf25=\E[1;5P, kf26=\E[1;5Q, kf27=\E[1;5R, kf28=\E[1;5S,

kf29=\E[15;5~, kf3=\EOR, kf30=\E[17;5~, kf31=\E[18;5~,

kf32=\E[19;5~, kf33=\E[20;5~, kf34=\E[21;5~,

kf35=\E[23;5~, kf36=\E[24;5~, kf37=\E[1;6P, kf38=\E[1;6Q,

kf39=\E[1;6R, kf4=\EOS, kf40=\E[1;6S, kf41=\E[15;6~,

kf42=\E[17;6~, kf43=\E[18;6~, kf44=\E[19;6~,

kf45=\E[20;6~, kf46=\E[21;6~, kf47=\E[23;6~,

kf48=\E[24;6~, kf49=\E[1;3P, kf5=\E[15~, kf50=\E[1;3Q,

kf51=\E[1;3R, kf52=\E[1;3S, kf53=\E[15;3~, kf54=\E[17;3~,

kf55=\E[18;3~, kf56=\E[19;3~, kf57=\E[20;3~,

kf58=\E[21;3~, kf59=\E[23;3~, kf6=\E[17~, kf60=\E[24;3~,

kf61=\E[1;4P, kf62=\E[1;4Q, kf63=\E[1;4R, kf7=\E[18~,

kf8=\E[19~, kf9=\E[20~, khome=\EOH, kich1=\E[2~,

kind=\E[1;2B, kmous=\E[<, knp=\E[6~, kpp=\E[5~,

kri=\E[1;2A, mc0=\E[i, mc4=\E[4i, mc5=\E[5i, meml=\El,

memu=\Em, mgc=\E[?69l, nel=\EE, oc=\E]104\007,

op=\E[39;49m, rc=\E8, rep=%p1%c\E[%p2%{1}%-%db,

rev=\E[7m, ri=\EM, rin=\E[%p1%dT, ritm=\E[23m, rmacs=\E(B,

rmam=\E[?7l, rmcup=\E[?1049l\E[23;0;0t, rmir=\E[4l,

rmkx=\E[?1l\E>, rmm=\E[?1034l, rmso=\E[27m, rmul=\E[24m,

rs1=\Ec\E]104\007, rs2=\E[!p\E[?3;4l\E[4l\E>, sc=\E7,

setab=\E[%?%p1%{8}%<%t4%p1%d%e%p1%{16}%<%t10%p1%{8}%-%d%e48;5;%p1%d%;m,

setaf=\E[%?%p1%{8}%<%t3%p1%d%e%p1%{16}%<%t9%p1%{8}%-%d%e38;5;%p1%d%;m,

sgr=%?%p9%t\E(0%e\E(B%;\E[0%?%p6%t;1%;%?%p5%t;2%;%?%p2%t;4%;%?%p1%p3%|%t;7%;%?%p4%t;5%;%?%p7%t;8%;m,

sgr0=\E(B\E[m, sitm=\E[3m, smacs=\E(0, smam=\E[?7h,

smcup=\E[?1049h\E[22;0;0t, smglp=\E[?69h\E[%i%p1%ds,

smglr=\E[?69h\E[%i%p1%d;%p2%ds,

smgrp=\E[?69h\E[%i;%p1%ds, smir=\E[4h, smkx=\E[?1h\E=,

smm=\E[?1034h, smso=\E[7m, smul=\E[4m, tbc=\E[3g,

u6=\E[%i%d;%dR, u7=\E[6n, u8=\E[?%[;0123456789]c,

u9=\E[c, vpa=\E[%i%p1%dd,

There’s so much junk in there. I wonder how much only applies to non-ANSI hardware terminals, and therefore is irrelevant these days.

For now, we’re only interested in three of these capabilities:

colorsis how many colors this terminal supports. The standard values are 0, 8, 16, 256, and 0x1000000 (24-bit), though other values exist.setafandsetabset foreground and background colors, respectively. I believe they stand for “Set ANSI Foreground” and “Set ANSI Background”. Each takes a single argument, the color number.

Those percent signs are a parameter arithmetic and substitution

language. Let’s decode setaf in particular:

setaf=\E[%?%p1%{8}%<%t3%p1%d%e%p1%{16}%<%t9%p1%{8}%-%d%e38;5;%p1%d%;m

print "\E["

if p1 < 8 {

print "3" p1

} else if p1 < 16 {

print "9" (p1 - 8)

} else {

print "38;5;" p1

}

print "m"

This is the xterm-256color terminfo description. It only knows how

to output the ANSI 30-37 SGR parameters, the non-standard 90-97

brights (from IBM AIX), or otherwise the 256-entry palette, using

ambiguous semicolon-delimited syntax.

Let’s compare with xterm-direct, the terminfo entry that supports

RGB.

$ infocmp xterm-256color xterm-direct

comparing xterm-256color to xterm-direct.

comparing booleans.

ccc: T:F.

comparing numbers.

colors: 256, 16777216.

comparing strings.

initc: '\E]4;%p1%d;rgb:%p2%{255}%*%{1000}%/%2.2X/%p3%{255}%*%{1000}%/%2.2X/%p4%{255}%*%{1000}%/%2.2X\E\\', NULL.

oc: '\E]104\007', NULL.

rs1: '\Ec\E]104\007', '\Ec'.

setab: '\E[%?%p1%{8}%<%t4%p1%d%e%p1%{16}%<%t10%p1%{8}%-%d%e48;5;%p1%d%;m', '\E[%?%p1%{8}%<%t4%p1%d%e48:2::%p1%{65536}%/%d:%p1%{256}%/%{255}%&%d:%p1%{255}%&%d%;m'.

setaf: '\E[%?%p1%{8}%<%t3%p1%d%e%p1%{16}%<%t9%p1%{8}%-%d%e38;5;%p1%d%;m', '\E[%?%p1%{8}%<%t3%p1%d%e38:2::%p1%{65536}%/%d:%p1%{256}%/%{255}%&%d:%p1%{255}%&%d%;m'.

A few things are notable:

xterm-directadvertises 16.7 million colors, as expected.xterm-directunsets thecccboolean, which indicates color indices cannot have new RGB values assigned.- Correspondingly, xterm-direct unsets

initc,oc, andrs1, also related to changing color values at runtime. - And of course

setafandsetabchange. We’ll decode that next.

Here’s where Terminfo’s limitations cause us trouble. Terminfo and ncurses are tied at the hip. Their programming model is that there are N palette entries, each of which has a default RGB value, and terminals may support overriding any palette entry’s RGB value.

The -direct terminals, however, are different. They represent 24-bit

colors by pretending there are 16.7 million palette entries, each of

which maps to the 8:8:8 RGB cube, but whose values cannot be changed.

Now let’s look at the new setaf:

print "\E["

if p1 < 8 {

print "3" p1

} else {

print "38:2::" (p1 / 65536) ":" ((p1 / 256) & 255) ":" (p1 & 255)

}

print "m"

It’s not quite as simple as direct RGB. For compatibility with

programs that assume the meaning of setaf, this scheme steals the

darkest 7 blues, not including black, and uses them for compatibility

with the basic ANSI 8 colors. Otherwise, there’s a risk of legacy

programs outputting barely-visible dark blues instead of the ANSI

colors they expect.

One consequence is that the -direct schemes are incompatible with

the -256color schemes, so programs must be aware that 256 colors

means indexed and 16.7 million means direct, except that the darkest 7

blues are to be avoided.

Fundamentally, terminfo has no notion of color space. So a program that was written before terminfo even supported more colors than 256 might (validly!) assume the values of the first 8, 16, or even 256 palette entries.

This explains an issue with the Rust crate termwiz that I recently ran into at work. A program expected to output colors in the xterm-256color palette, but was actually generating various illegibly-dark shades of blue. (Note: Despite the fact that the issue is open as of this writing, @quark-zju landed a fix, so current termwiz behaves reasonably.)

This is a terminfo restriction, not a terminal restriction. As far as I know, every terminal that supports 24-bit color also supports the xterm 256-color palette and even dynamically changing their RGB values. (You can even animate the palette like The Secret of Monkey Island did!) While I appreciate Thomas Dickey’s dedication to accurately documenting history and preserving compatibility, terminfo simply isn’t great at accurate and timely descriptions of today’s vibrant ecosystem of terminal emulators.

Kovid Goyal, author of kitty, expresses his frustration:

To summarize, one cannot have both 256 and direct color support in one terminfo file.

Frustrated users of the ncurses library have only themselves to blame, for choosing to use such a bad library.

A deeper, more accurate discussion of the challenges are documented in kitty issue #879.

In an ideal world, terminfo would have introduced a brand new capability for 24-bit RGB, leaving the adjustable 256-color palette in place.

Modern programs should probably disregard most of terminfo and assume that 16.7 million colors implies support for the rest of the color capabilities. And maybe generate their own ANSI-compatible escape sequences… except for the next wrinkle.

Setting TERM: Semicolons Again!

Gripes about terminfo aside, everyone uses it, so we do need to ensure TERM is set correctly.

While I’d like to standardize on the colon-based SGR syntax, several terminals I use only support semicolons:

- Conhost, Windows’s built-in console.

- Mintty

claims to

work

(and wsltty does), but for some

reason running my colortest.rs

program

from Cygwin only works with semicolon syntax, unless I pipe the

output through

cator a file. There must be some kind of magic translation happening under the hood. I haven’t debugged. - Mosh is aware, but hasn’t added support.

- PuTTY.

- Ubuntu 22.04 LTS ships a version of Konsole that only supports semicolons.

Terminfo entries are built from “building blocks”, marked with a plus.

xterm+direct

is the building block for the standard colon-delimited syntax.

xterm+indirect

is the building block for legacy terminals that only support semicolon

syntax.

Searching for xterm+indirect shows which terminfo entries might work

for me. vscode-direct looks the most accurate. I assume that, since

it targets a Microsoft terminal, it’s probably close enough in

functionality to Windows Terminal and Windows Console. I have not

audited all capabilities, but it seems to work.

The next issue was that none of my servers had the -direct terminfo

entries installed! On most systems, the terminfo database comes from

the

ncurses-base

package, but you need

ncurses-term

for the extended set of terminals.

At work, we can configure a default set of installed packages for your

hosts, but I have to install them manually on my unmanaged personal

home machines. Also, I was still running Ubuntu 18, so I had to

upgrade to a version that contained the -direct terminfo entries.

(Of course, two of my headless machines failed to boot after

upgrading, but that’s a different story.)

Unfortunately, there is no terminfo entry for the Windows console.

Since I started writing this post, ncurses introduced a

winconsole

terminfo entry, but it neither supports 24-bit color nor is released

in any ncurses version.

Configuring Emacs

Emacs documents how it detects truecolor support.

I find it helpful to M-x eval-expression (display-color-cells) to

confirm whether Emacs sees 16.7 million colors.

Emacs also documents the -direct mode terminfo limitation described

above:

Terminals with ‘RGB’ capability treat pixels #000001 - #000007 as indexed colors to maintain backward compatibility with applications that are unaware of direct color mode. Therefore the seven darkest blue shades may not be available. If this is a problem, you can always use custom terminal definition with ‘setb24’ and ‘setf24’.

It’s worth noting that RGB is Emacs’s fallback capability. Emacs

looks for the setf24 and setb24 strings first, but no terminfo

entries on my machine contain those capabilities:

$ for t in $(toe -a | cut -f1); do

if (infocmp "$t" | grep 'setf24') > /dev/null; then

echo "$t";

fi;

done

$

Nesting Terminals

conhost.exe (WSL1)

+-------------------------+

| mosh |

| +---------------------+ |

| | tmux | |

| | +-----------------+ | |

| | | emacs terminal | | |

| | | +-------------+ | | |

| | | | $ ls | | | |

| | | | foo bar baz | | | |

| | | +-------------+ | | |

| | +-----------------+ | |

| +---------------------+ |

+-------------------------+

I’d never consciously considered this, but my typical workflow nests multiple terminals.

- I open a graphical terminal emulator on my local desktop, Windows, Mac, or Linux.

- I mosh to a remote machine or VM.

- I start tmux.

- I might then use a terminal within Emacs or

Asciinema or GNU

Screen.

- Yes, there are situations where it’s useful to have some screen sessions running inside or outside of tmux.

Each of those layers is its own implementation of the ANSI escape sequence state machine. For 24-bit color to work, every single layer has to understand and accurately translate the escape sequences from the inner TERM value’s terminfo to the outer terminfo.

Therefore, you need recent-enough versions of all of this software. Current LTS Ubuntus only ship with mosh 1.3, so I had to enable the mosh-dev PPA.

TERM must be set correctly within each terminal: tmux-direct within

tmux, for example. There is no standard terminfo for mosh, so you

have to pick something close enough.

Graphical Terminal Emulators

Most terminals either set TERM to a reasonable default or allow you to override TERM.

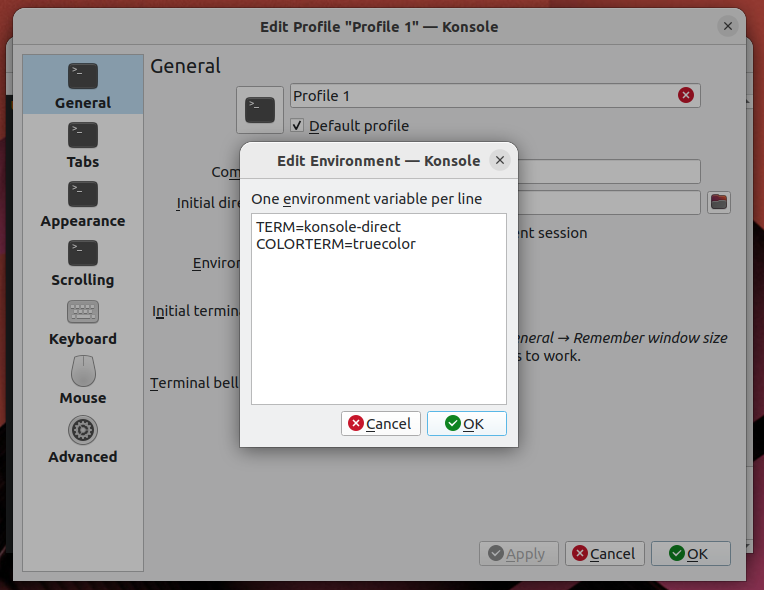

I use Konsole, but I think you could find a similar option in whichever you use.

ssh

Often, the first thing I do when opening a terminal is to ssh

somewhere else. Fortunately, this is easy, as long as the remote host

has the same terminfo record. ssh carries your TERM value into the

new shell.

tmux

But then you load tmux and TERM is set to screen! To fix this,

override default-terminal in your ~/.tmux.conf:

set -g default-terminal "tmux-direct"

For extra credit, consider setting tmux-direct conditionally with

%if when the outer TERM supports 24-bit color, otherwise leaving the

default of screen or tmux-256color. And then let me know how you

did it. :P

mosh

While recent mosh does support 24-bit color, it only advertises 8 or 256 colors. Thus, it’s up to you to set TERM appropriately.

Mosh aims for xterm compatibility, but unfortunately only supports

semicolon syntax for SGR 38 and 48, so TERM=xterm-direct does not

work. So far, I’ve found that vscode-direct is the closest to

xterm-direct.

There is no convenient “I’m running in mosh” variable, so I wrote a

detect-mosh.rs

Rust script and called it from .bashrc:

unamer=$(uname -r)

unameo=$(uname -o)

if [[ ! "$TMUX" ]]; then

if [[ "$unamer" == *Microsoft ]]; then

# WSL 1

export TERM=vscode-direct

elif [[ "$unameo" == Cygwin ]]; then

# Eh, could just configure mintty to set mintty-direct.

export TERM=vscode-direct

elif detect-mosh 2>/dev/null; then

# This should be xterm-direct, but mosh does not understand SGR

# colon syntax.

export TERM=vscode-direct

fi

fi

It works by checking whether the shell process is a child of

mosh-server.

The jury’s still out on whether it’s a good idea to compile Rust in the critical path of login, especially into an underpowered host like my Intel Atom NAS or a Raspberry Pi.

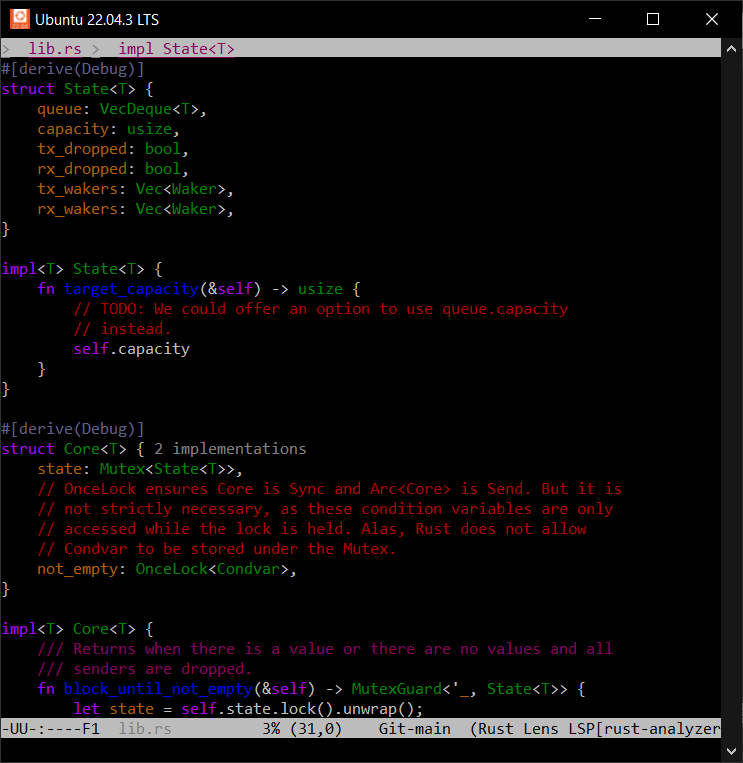

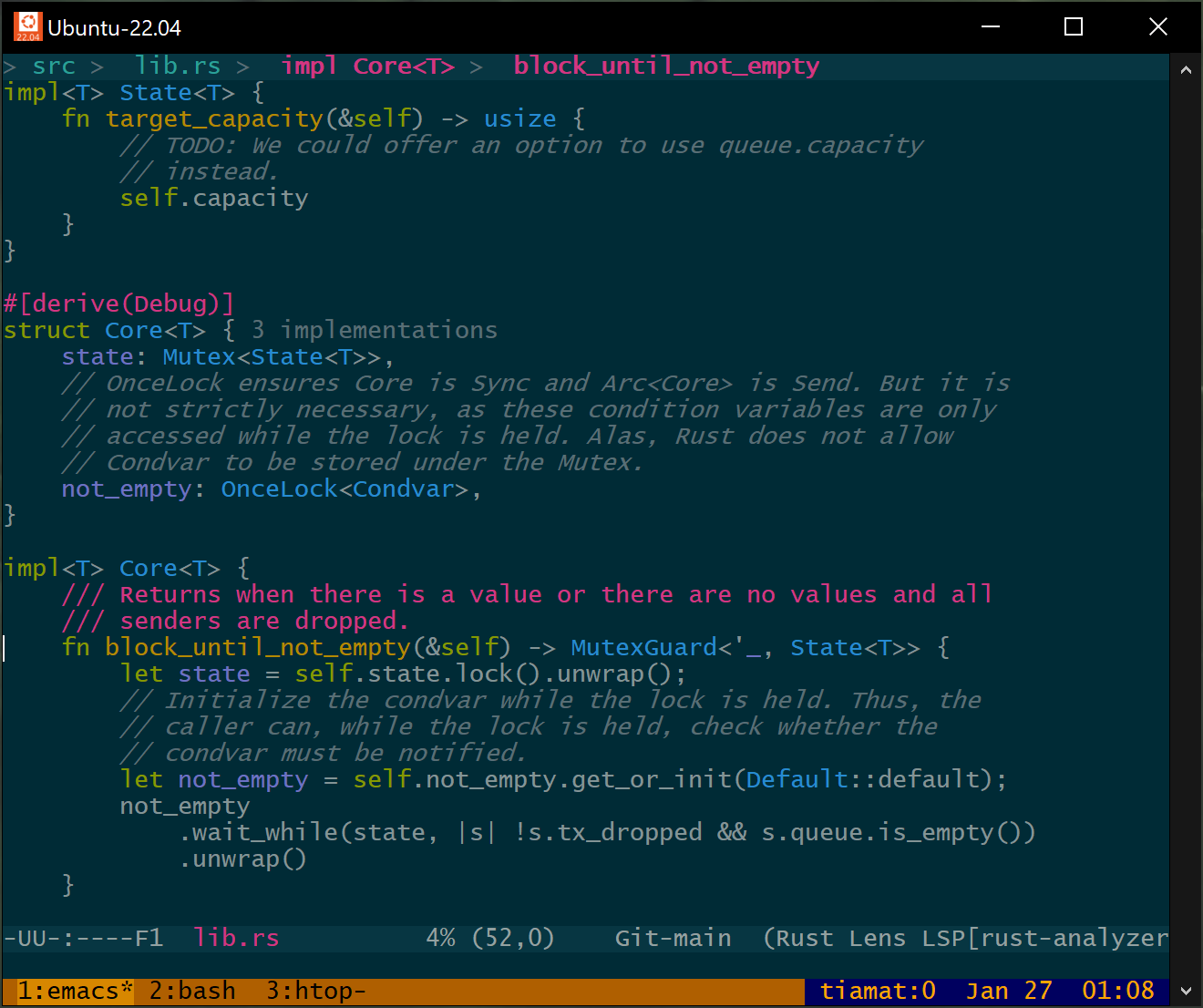

It Works!

Beautiful Emacs themes everywhere!

This was a ton of work, but I learned a lot, and, perhaps most importantly, I now feel confident I could debug any kind of wonky terminal behavior in the future.

To recap:

- Terminals don’t agree on syntax and capabilities.

- Terminfo is how those capabilities are queried.

- Terminfo is often limited, sometimes inaccurate, and new terminfo versions are released infrequently.

What’s Next?

If you were serious about writing software to take full advantage of modern terminal capabilities, it would be time to break from terminfo.

I imagine such a project would look like this:

- Continue to use the TERM variable because it’s well-supported.

- Give programs knowledge of terminals independent of the age of the

operating system or distribution they’re running on:

- Programs would link with a frequently-updated (Rust?) library.

- Said library would contain a (modern!) terminfo database representing, say, the last 10 years of terminal emulators, keyed on (name, version). Notably, the library would not pretend to support any hardware terminals, because they no longer exist. We can safely forget about padding, for example.

- Continue to support the terminfo file format and OS-provided terminfo files on disk, with some protocol for determining which information is most-up-to-date.

- Allow an opt-in TERMVERSION to differentiate between the capabilities of, for example, 2022’s Konsole and 2023’s Konsole.

- Allow describing modern terminal capabilities (like 24-bit color, 256-color palette animation, URL links, Kitty’s graphics protocol) in an accurate, unambiguous format, independent of the timeline of new ncurses releases.

- Backport modern terminal descriptions to legacy programs by

providing a program to be run by

.bashrcthat:- Uses TERM and TERMVERSION to generate a binary terminfo file in

$HOME/.terminfo/, which ncurses knows how to discover. - Generates unambiguous 24-bit color capabilities like

RGB,setf24, andsetb24, despite the fact that getting them added to terminfo has been politically untenable. - Otherwise, assumes RGB-unaware programs will assume the 256-color

palette, and leaves

colors#0x100,initc,ocin place. Palette animation is a useful, widely-supported feature.

- Uses TERM and TERMVERSION to generate a binary terminfo file in

Let me know if you’re interested in such a project!